04 Aug How Laws Replaced Our Virtues

Looking out over an ocean of colorful faces and blue uniforms, I see a room-full of prisoners inside San Quentin Prison. All shades of flesh color the room, from dark blue-black to the brightest lily white, and every shade of brown, beige and tan. Their ages range from early twenties to late sixties. These men have served serious time ‘inside,’ and are near the date of their release. Gary Shimel, the brilliant and caring Director of the Pre-Release Education program, invited me to speak to his class. The men are alert and listening intently.

I wrote the words Happiness on the whiteboard, saying: “Virtues are behaviors that result in happiness for yourself and others. What are some of the ways you can behave that make you and others happy?”

They call out from around the room: “Honesty.” “Integrity.” “Kindness.” “Cooperation.” “Love.” “Faith.” “Patience.” I write their answers on the board in a vertical column.

One man called out loudly: “Sex!” and there was friendly laughter all around. “Yes,” I said as I wrote it on the board. “Sex can make us happy, and it can make the other person happy, too – when it’s kind and loving, and when there’s mutual desire and respect. When any of those elements are lacking, it can be a source of pain and suffering. Right?” There were nods around the room along with thoughtful silence. “What are other ways of acting that produce happiness in you and others? How do others treat you that make you feel good?”

“Respect!” said one Latino man, and there were again nods – this time all around. “Good,” I said. “Respect is one of those virtues that has to go both ways. You have to give it to get it, right?” There were more nods in agreement.

I wrote the word Unhappiness on top of the second column. “What behaviors make you and others unhappy?” I asked. “What causes suffering?” The answers came in fast: “Disrespect.” “Cheating.” “Violence.” “Theft.” “Breaking the law.” “Doing drugs.”

Some of these men had been convicted of non-violent offenses such as drug use or dealing. Others had been convicted for violent acts. They were simply men – men who had messed up their lives, or gotten caught up in someone else’s mess. My guess was that most of them had childhood experiences we wouldn’t wish on any child. They had been punished. They had done their time. They deserved my respect.

They would soon be leaving San Quentin to return “Outside” – to the world and society. What could I tell them that would help them survive, or possibly thrive? Could I help prevent their return? I hoped that some of them might take away a bit of wisdom, a new idea, or some new options after being released from prison.

Recidivism rates are high in California – two-thirds of California’s offenders return to prison within three years. More than 50% of those offenders are sent back for parole violations alone, a rate considerably higher than in other large states. Is it possible that a little understanding, a bit of philosophy, could improve their chances?

I continued my pitch: “Philosophy comes from two Greek words, philos, meaning love, and sophia, meaning wisdom. So philosophy means the love of wisdom. Early philosophers spent their time trying to understand the world and people. They realized that they could use happiness as a kind of measuring device. They noticed, just like you, that there are many things we can do to cause suffering – in ourselves or others, and they labeled these Vices,” I said, writing the word on the board. “As in ‘Vice Squad.’” There were murmurs of quiet laughter. “What are some other ways of causing suffering and unhappiness?”

“Hatred,” said one man. “Getting into fights,” said another. “Anger.” “Cheating on your girlfriend.” “Lying.” “Drinking too much.” I wrote each one on the board, creating a long list.

“Great!” I said. “You guys know what makes you happy and unhappy. You know what makes others happy and unhappy. You want to be happy, right?” Many nods of agreement. “Okay, so then why do we do things that make ourselves and others unhappy? And why do we have so many laws? Where did laws come from in the first place? And why do so many people break them? And how did you end up inside this prison when there are so many other people breaking laws that aren’t here?”

There were stares and blank looks. Curiosity, but no answers. This is the expected result of asking a long series of questions. It’s a trick used by public speakers and orators, giving the speaker some space to collect his thoughts before launching into the next piece of lecture material, “I’m going to tell you the story of virtues, values and vices, and how laws came to replace happiness…”

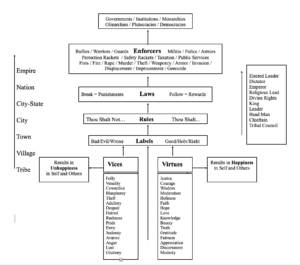

I began weaving the story of human civilization. This is how Virtues, the inner guide to happiness, become rules, and how rules become laws. The end result of this tale is that 1% of the U.S. population is now incarcerated. Are we a particularly terrible people? An evil culture? A bad civilization?

Philosophers of every previous time and culture have discussed morality. Morals are a culture’s guide for proper behavior – and the basis for how to live a good life. Each culture defines its own values, virtues and vices – specifying how members of that culture should treat each other, themselves, and the world around them.

Virtues are traits in a person or behavior that are valued as being good. The word virtue is derived from Latin, signifying manliness or courage. In its widest sense, virtue refers to excellence. The conceptual opposite of virtue is vice, which signifies the absence, or opposite, of excellence.

For thousands of years, intelligent people have attempted to identify what constitutes “the good life.” Like all good social scientists, they observed the behavior of people and examined the results. Some ways of living seemed to consistently produce a good life. Others ways of living produced suffering or unhappiness. These behaviors were divided into virtues and vices. Greek philosophers identified four cardinal, or “hinge” virtues: Justice, Courage (fortitude), Wisdom (prudence), and Moderation (temperance). Plato added Holiness as a virtue. Jewish and Christian philosophers added three supernatural virtues: Faith, Hope, and Unselfish Love (agape, or charity). Modern philosophers have added many other virtues, including Knowledge, Discernment, Courage, Humanity, Transcendence, Appreciation, Beauty, Gratitude, Modesty, Fairness, and Integrity.

Vices, the opposite (or absence) of virtues, include Folly, Venality, Cowardice, Blasphemy, Theft, Adultery, Despair, Hatred, Rashness, Over-cautiousness, and Narrow-mindedness. The Catechism of the Catholic Church identifies the Capital Vices (the famous “7 Deadly Sins”) as Pride, Envy (covetousness or jealousy), Avarice (greed), Anger, Lust, Gluttony, and Sloth (laziness).

Throughout time, both vices and virtues became codified (literally, “solidified as a code”) into a set of rules for “proper” or “right” behavior. Instead of educating children to look within themselves and intelligently observe what caused happiness, it was easier (and more efficient) to give them rules to follow. Do this. Don’t do that. Virtuous behavior was reinforced and rewarded in the family and the community with approval, love, belonging, and recognition. Because our brain/minds are programmed to believe our betters and elders, we naturally accept whatever programming comes our way from our parents, teachers, and those in positions of authority. In addition, a primitive drive is to belong, and we’ll do anything to achieve it, including shaping ourselves to fit other’s expectations. Even apes seek “favors” or recognition from the alpha male and female in the troop.

As villages and small communities evolved into city-states, a hierarchical power structure evolved to manage the complexities of civilized life. Those who were in power treated their subordinates – the peasants – in the same way as parents treated their children: they gave them rules to follow. Those who cooperated were granted additional rewards, such as increased power, position, role, authority, status, or wealth.

When earthly rewards ran out, or no longer worked as incentives, heavenly rewards were created, and these became powerful manipulation tools over large populations. This included salvation and elevated status after death. Being chosen to sit at the right hand of God is a powerful motivator, as is being rewarded with dozens of virgins in the Islamic version of Heaven. In Pagan and Eastern religions, the Fates, Gods or Goddesses could grant boons or blessings if you did the right things – which included conducting ceremonies, making offerings or sacrifices, reciting prayers, or making promises.

In both religious and secular settings, vices were discouraged with threats of punishment. Punishments were doled out along a spectrum of seriousness, from mild to extreme. At the light end, you could expect criticism or ostracism from the group. At the severe end, you would be tortured or killed. Because the threat of death did not seem to stop some unacceptable behaviors, the severity of punishment went beyond death to eternal damnation. Even in tribal cultures, the ancestors sat in judgment of behavior, and knowing that you would meet them after death, there was additional incentive to behave properly.

As civilizations developed, moral codes turned into rules. Rules were further codified into laws, a set of codes that could be enforced. Creating and enforcing laws was a privilege and an expression of power by the Head Man – a King, Emperor, Ruler or Regional Tyrant. To enforce his laws, he employed paid bullies, a militia, or a police force. Consequences were laid out for violations of the laws of the land. Enforcers ensured that the populace was intimidated into carefully following the laws. Violators were prosecuted. Those who attempted to live outside the law were rounded up and killed. “Outlaws” were threats to the existing power structure, and had to be eliminated. It doesn’t take many examples for people to understand which way the wind is blowing. The Romans became experts at making examples of violators until the entire population cooperated with their rule.

Some groups successfully lived outside the law: Rulers and the Privileged Class (oligarchs: oligarchy is rule by the wealthy class). Privilege comes from Latin meaning “private law.” The Laws of the Land were for the common people. Those with power and wealth could do whatever they wanted. They lived outside the common law. They had rank – and rank has its privileges. A parody of The Golden Rule was created to describe this: “He who has the gold, makes the rules.”

The other group that lived outside the law were known as “outlaws.” There were always rebels against the “natural order” imposed by those on top. Rebels have always been with us, and their stories have become heroic myths, such as Robin Hood, Moses, and Spartacus.

Another kind of law and rule emerged from the Abrahamic religions, beginning with the Egyptian pharaoh Aten, the first monotheist. It is possible that Abraham, the founder of the Jewish religion, adopted monotheism from the Egyptians during Aten’s rule. The Jewish fathers claimed a special relationship with God, who informed them directly of the One God’s wishes, rules and plans. Laws were now issued from “on high” – the ultimate authority. God, the Divine King, was beyond human questioning. There was one truth that came from the very Source of Life, eternal and unchanging. Prior to monotheism, most cultures were polytheistic. There were many gods to pray to, from family ancestors to the forces of Nature. Tolerance was the rule – I’ll respect your gods if you respect mine. Monotheism was the beginning of religious intolerance: “Worship my God, in my way, or you die.” When these faith-based cultures merged with the political and economic power of kingdoms such as Rome, they became true empires, controlling not only the external behavior and exchange of their people, but also their internal belief structures and faith. The most successful merger in human history was Constantine’s merger of Roman military and secular rule with the faith-based rule of Christianity. The Church of Rome was born, and today remains one of the most powerful and wealthy kingdoms in the world, transcending the borders and laws of nearly every country in the world.

The Inner Compass

Greek philosophers asked the important question, “What creates (or constitutes) the good life?” (in Greek, totem bonem, or total good.) The same inquiry could be framed today: “What will make me happy?” For millennia, it has been demonstrated that when a person lives a virtuous life, he or she is much more likely to be happy.

It is easier to follow a rule or law than to investigate your own internal structure, or question your belief systems. People who follow laws and rules experience fewer punishments and negative consequences. When our parents exhorted us to follow the rules and avoid breaking the law, they were providing good advice with good intentions for our well-being. If your life is lived inside the rules, you can use the rules to your advantage. There are rewards for good behavior. Energy spent bucking the rules is usually unproductive in the long run. People who follow socially acceptable rules of etiquette are liked and invited back. If you spend time with those powerful people who made up the rules, or you find a way to serve them, you may earn the right to your own privileges. A phrase from the military (which my father used constantly to his own advantage) is RHIP: Rank Has Its Privileges.

Everyone I’ve met has a bit of the Rebel inside of them, however. There is something in us that chafes against authority, rebels against control, and fights for the expression of our own will. The Catholic Church attempted to rid people of that pesky free will. They borrowed the Pagan’s willful, sexy, native earth god Pan, and turned him into a vicious beast that violated God’s own Laws. This Devil, they said, then infiltrated every human mind with the absurd notion that we can choose for ourselves. This is a very bad idea if your goal is to control entire populations. “The devil made me do it!” was a common method of assigning blame for any bad behavior. Virtuous lives were rewarded in Heaven, they taught, and lives of Vice (vicious) were punished with eternal damnation in Hell. Death itself was no longer enough of a threat, apparently, to keep people in line – whether to pay their taxes to the King or to make their contributions to the Church.

Thus, the four main privileges, Money, Power, Sex, and Salvation, became intertwined. The Church worked in cahoots with the King and both prospered. Politicians worked in cahoots with the wealthiest individuals to pass laws favorable to them. If you had money, you could buy sex. If you had power, you could trade it off piecemeal for wealth. If you had sex to offer (either as a woman, or as a man with access to women), you could gain money or power. And salvation was the ultimate offer in exchange for sex, power, and wealth. Privilege represented the true Golden Rule: He who has the gold makes the rules. The wealthy don’t have to be virtuous. They can buy their way into Heaven.

In our complex, multi-everything society, our goal is to learn how to all get along with each other. It has been demonstrated that this is possible, but it requires great care, compassion, and tolerance for others’ choices and ways of life. What we all have in common, despite different moral codes, is that we all want to be happy. The U.S. was founded under the principle and value of individual freedom and the right to pursue happiness. How can we do this?

We can go back to the original definition of values, virtues and vices, and examine our own internal moral compass. What brings happiness to myself and others? What brings suffering to myself and others? “A creation (communication, idea, product or service) is ethical to the degree that it is considered valuable by those most directly affected by it.” (Harry Palmer, The Avatar Materials) At their core, all religious traditions share some form of the Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Do what makes you and others happy. If there were suddenly no rules and no laws, that would suffice to allow us to get along with each other. At least, until a new Boss Man emerged with his bullies to impose his (or her) particular moral code on the rest of us.

To be free, develop your Virtues, and live by your own Code. And also live and act within the rules and laws of your country – so you don’t get your vote – and your freedom – cancelled.

Click a button above to share this post with your friends and family

No Comments